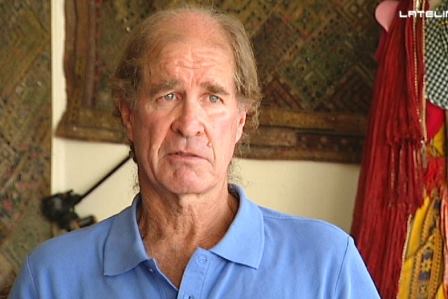

James Ricketson.

Australian director, James Ricketson, has written an open letter to IF on recent moves by Austrailan screen funding bodies and guilds to address the issue of gender diversity in the screen sector. It follows Australian actor Simone Ball's open letter on the subject of gender equity.

Read Simone's letter here

“Screen Australia is considering a radical push for a quota to ensure 50 per cent of the directors of funded films are women.”

– Sydney Morning Herald

Would such a quota result in better Australian films?

"It's ridiculous," says Gill Armstrong. "It's been 30 years since Jane Campion and I went through a glass ceiling and I feel there haven't been enough people following us."

Did Gill or Jane (Jocelyn Moorhouse should be on this list) rise to and break through the ‘glass ceiling’ as a result of quotas or because they were talented directors?

A question worthy of discussion, debate? I think so.

Between 2009 and 2014, Rosemary Neill’s ‘Gender Agenda’ article tells us, only 15 per cent of Australian feature films were directed by women.

Is this a problem? Were women directors being discriminated against?

Between 2009 and 2014 three of the key Screen Australia decision makers vis a vis feature film production were women.

Is the fact that they only greenlit 15 per cent feature films with women directors evidence that Ruth, Fiona and Martha (along with the heads of state film funding bodies, mostly women) were discriminating against female directors?

Or did this cohort of largely female film bureaucrats recommend feature projects to the Screen Australia board (amply represented by women – Claudia Karvan, Rachel Perkins and Rosemary Blight amongst others), because they believed them to be the best, regardless of the gender of the director?

59 per cent of documentary projects funded by Screen Australia during this same period had woman directors.

Is this evidence of gender bias in documentary? Or does it suggest that women were submitting documentary projects of a higher quality than men?

Will there be a call by the Screen Director’s Guild and Screen Australia to rectify gender inequity in the documentary sector? 50/50 quotas for male and female documentary directors?

Out of context, raw statistics such as those quoted in ‘Gender Agenda’ (15 per cent women directors) tell us little.

90 per cent of nurses are women? Is this because men are discriminated against in the nursing profession? Or is it because there are other factors that draw more women to nursing than men?

There are more female than male journalists, authors, teachers, lab technicians, therapists, editors, librarians and insurance underwriters? Are men being discriminated against in these professions or is it simply that more women than men are attracted to them?

Could it be that more women are drawn to documentary filmmaking than men and that there is not a problem that needs to be rectified?

What proportion of feature film projects submitted to Screen Australia for investment funding had women directors attached, compared to those with male directors?

If , say, only 15 per cent of feature films recommended by Screen Australia for investment funding had women directors attached, ‘only’ 15 per cent of feature films with women directors is evidence of gender equality; not inequality. The same applies, of course, if 59 per cent of documentary projects submitted to Screen Australia had women directors.

Statistics can be made to tell almost any story that suits the agenda of those using them. Imagine the following hypothetical scenario:

10 feature projects are submitted to Screen Australia for investment funding.

Owing to SA budgetary constraints only 3 can receive funding.

All 10 projects are of roughly equal quality; all deserving of funding.

Eight of the projects have male directors attached; two have female directors.

Screen Australia greenlights two projects with male directors and one with a female director.

This statistic can be looked at in two ways:

(1) Male directors have twice the opportunities (2:1) of women directors.

(2) Male directors have a 25 per cent chance (one in four) of getting their project funded whilst women directors have a 33 per cent chance (one in three) of receiving funding.

This same statistic could be used by both men and women to ague that they were being discriminated against.

As Benjamin Disraeli said (or was it Mark Twain?) “There are lies, damned lies and statistics.”

Playing the statistics game a little longer:

2.4 per cent of Australians identify as Aboriginal, whilst 2.2 per cent of Australians are Muslim.

Aboriginal directors receive infinitely more funding than Muslim directors? Is this fair? Are Muslim directors being discriminated against? In the interests of equity, shouldn’t Muslim directors (filmmaking teams) receive as much funding as Aboriginal directors/teams?

And what about the 2 per cent of Australians who are gay? Shouldn’t there be almost as many feature films made by gay directors as by Aboriginal directors? And what about disabled directors, directors suffering from a mental illness, transgender directors? And so on.

Whilst on the subject of statistics:

Imagine a funding world, the one espoused by the Australian Director’s Guild, in which 50 per cent of feature film directors must be women.

A hypothetical but highly probably scenario:

Screen Australia conducts an assessment round in which (money is tight) only 10 projects with directors attached can receive script development monies. The 7 projects deemed by SA Project Managers to be of the highest quality have women writers and directors attached. Only 3 in the ‘top 10’ have have male writers and directors attached.

In accordance with the 50/50 policy espoused by the Australian Director’s Guild, script development monies must be split evenly between projects with male and female screenwriters; male and female directors.

So, two of the female screenwriter/director teams must, in the interests of equal opportunity, be knocked back whilst two projects of lesser quality, developed by men, receive funding.

Would this be fair?

And if the same principle is applied to documentary, should a Gill Armstrong documentary be knocked back in order to meet a 50/50 doco quota in favour of a male directed doco of lesser quality? (How would you feel about this, Gill?)

Should this equal opportunity concept be applied to all groups within society who feel, quite justifiably perhaps, that they are inadequately represented when it comes to funding decisions? If transgender, disabled, mentally ill, Muslim etc (fill in the minority group of your choice) filmmakers say, "How come we never receive funding? We feel discriminated against!" how will the Australian Director’s Guild respond? What argument will the ADG (and Screen Australia) mount in support of the proposition that equity applies to the gender of directors but not to sexual orientation, religious affiliation or class?

Class!

Yes, why not?

“…I am also concerned about class,” says Kate Cherry, Black Swan artistic director, “I think that is going to be our next issue.”

Once the 50/50 male/female director goal has been achieved, will the next goal be 50 per cent privately schooled filmmakers and 50 per cent state school filmmakers? 50 per cent middle class directors/50 per cent working class directors?

I am only half-joking!

Once the quota concept has taken hold, become an integral part of our thinking, where do we stop thinking in terms of quotas without seeming to be discriminatory?

Is this an equal opportunity Pandora’s Box we filmmakers want to open? Do we want to see, in any one year, films made by a rainbow coalition of directors representing different interest groups?

A feature film with a transgender Muslim director may well get ticks in lots of boxes, but if it is a second rate film, if if fails to put bums on seats, will we not, as an industry, have shot ourselves in the foot?

Might a quota system working against our long term interests, even if it does elicit the short term warm inner glow that accompanies behaving in a politically correct way?

Will the questions raised here be discussed, debated, amongst film and TV story-tellers? Or will the Australian Director’s Guild (pushing hard for a gender-based quota for feature film directors) and government film bureaucrats take it upon themselves to impose their quota-inspired ideas on the rest of us – hoping that we filmmakers will not want to be branded as ‘sexist’ if we think that the imposition of quotas is a bad idea?